Discovery Report

Discovery Report

March 2022

The 'Why'

In Scotland there is huge demand across sectors to engage with people with lived experience in a way that is safe, trauma informed and not tokenistic, with an understanding that lived experience must be at the ‘heart and start’ of all systems and services. However, policy makers and practitioners within local authorities, and other community planning organisations, recognise that they require support to embed this approach, particularly when working with those who have experienced trauma due to gender-based violence.

According to Victim Focus (2021),1 out of 58 respondents in their study looking at participation activities, only 9% had ever been paid, or had their expenses reimbursed, despite being asked to retell their traumas more than 25 times each. Only 7% had ever been offered psychological support, counselling, debriefing or emotional support after retelling their experiences. From speaking with victims and survivors, we know that they are, too often, asked to ‘rate, not create’ - and some survivors report that they don’t see or hear about the changes that occur after sharing their voice. This can lead to survivors feeling used, dismissed or, in some cases, retraumatised. Often the experiences of survivors from marginalised backgrounds are ignored. If we exclude survivors from the response to domestic abuse, the consequences can be severe: costly and ineffective services, stress and low morale for professionals, poor-quality policymaking and commissioning, repeating cycles of abuse, lack of justice, serious or fatal injury for victims and the lifelong psychological impact of living with control and/or violence.

We believe people who speak about their experiences should be believed, validated and their experience valued as ‘expertise’ and as a method of creating social change.

Authentic Voice: Embedding Lived Experience in Scotland is a programme led by SafeLives, Improvement Service and Resilience Learning Partnership in partnership with survivors of domestic abuse and trauma and funded by the Scottish Government. The programme aims to:

Support women with experience of domestic abuse and other forms of complex trauma to use their experiences to help shape the pathways to support and service delivery.

Enable professionals working across a wide range of policy areas to embed survivor voice and lived experience into system and service design processes in a high quality, sustainable and trauma-informed way.

Help decision-makers to see how meaningful change can be achieved and compel them to act, through seeing living examples, having access to evidence and hearing diverse voices of people with lived experience.

Work with the Authentic Voice Panel who will provide oversight, guidance and ensure all our activities are rooted in survivor voice.

This Discovery Report is the culmination of the first phase of this programme, where we learnt how survivor voice and lived experience is currently used in organisations across Scotland. We know that there is a clear understanding of the importance of survivor voice, and we heard incredible examples of innovative work happening across sectors.

This report is not intended to give a complete picture of all the lived experience work that is currently being undertaken in Scotland. Rather, it aims to set out some of the themes we heard, looking at what works, the challenges, and what is needed to fully embed lived experience and participation.

As this project continues, we intend to talk to more services about their experiences, as well as with survivors themselves, to enable us to share insight and survivor led resources to organisations to ensure that the lived experience work they are undertaking can be embedded fully, effectively, and safely.

A note about language – within this report we refer to lived experience and survivor/victim voice as agreed by the SafeLives Authentic Voice Panel, however different sectors and organisations may use other terms when describing their own activities. ‘Authentic Voice’ is a term developed and used within SafeLives, referring to lived experience of domestic abuse.

What we learned - a summary

The findings from this discovery exercise highlight that:

It is clear that there is a need for dedicated resources for lived experience work, as well as an increased opportunity for training, and joined up working across organisations/services. More consideration should be given to those within systems/ organisations as staff survivors/ lived experience experts. This support would help to develop lived experience activities and fully embed this work into services/organisations/systems in a sustainable way.

There is a wide range of lived experience activities being carried out across Scotland. The most common activity that survivors are involved in, is providing advice and guidance to services on the projects and workstreams that they were undertaking.

Some lived experience work is directly funded, while other activities are embedded in wider projects and/or supported by partner organisations.

A trauma informed approach is paramount when working with lived experience participants to ensure they receive wraparound care and can request particular support if needed.

Lived experience work was described as being ‘empowering’ and improving the confidence and self-esteem of participants.

There are some concerns that lived experience work can be tokenistic and avoids exploring the complex issues experienced by survivors.

The majority of activities were focussed on ‘service users’ rather than professionals with lived experience of trauma.

Who we spoke to

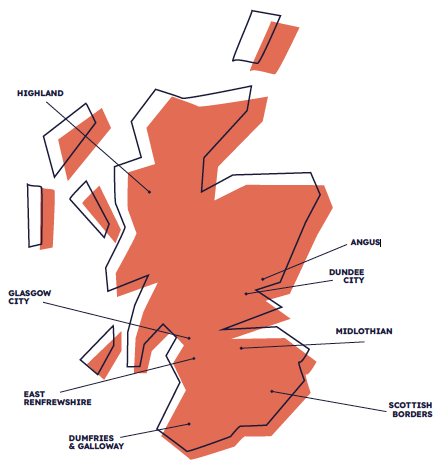

In total, we spoke to 18 organisations that work across Scotland in a variety of sectors. The organisations were geographically spread across the country, with eight working nationwide, three in the Glasgow City area, and one each in the areas of Angus, Dumfries and Galloway, Dundee City, East Renfrewshire, Highland, Midlothian and the Scottish Borders.

Over half of the organisations worked in the Violence Against Women & Girls (VAWG) sector, with ten of them being services focusing on domestic abuse, sexual abuse and/or another specialist VAWG area. There was also a range of other sectors that services were involved in, including two in housing, one in mental health, one in foster care, one in violence reduction, one supporting victims of crime, one supporting BME women, one supporting refugees and migrants and one supporting those involved in the sex industry.

What we heard

We also spoke to one funding organisation, and one multi-sector partnership. One of the services we spoke to was statutory, while the other 17 were all located in the voluntary/third sector.

Almost all of the services we spoke with were currently undertaking lived experience work, and the only two services that were not currently doing this were in the planning stages of starting lived experience work.

The most common activities that those with lived experience were involved in was in providing advice and guidance to services on the projects and workstreams that they were undertaking.

This took the form of:

sitting on advisory groups, forums and steering groups to shape the overall strategy and delivery of services

consultations for specific projects

involvement in funding panels, staff recruitment

research, project evaluations and creating resources such as guides for staff/service users

Another common activity that those with lived experience were involved in was direct peer support with other survivors who were being supported by the service.

This took the form of:

mentoring

befriending

community drop ins and group work

Policy and campaigning activities were also highlighted as an important role for survivors and those with lived experience.

This took the form of:

Supporting the organisation’s policy team

Speaking directly to those in positions of power such as government ministers

Public facing work including speaking at events/writing blogs and magazine articles

A small number of organisations also said that a proportion of their employees had lived experience and were therefore involved in all of their activities. This will be explored further as the project continues, as the need to ensure there are no ‘them and us’ divisions is something that came out strongly in the discovery work.

A variety of methods were used by organisations to engage people with lived experience in their participation activities.

These included:

Recruiting only current service users within an organisation.

Participants recruited through partner agencies.

Open, public-facing recruitment.

Engaging with previous service users.

Recruiting staff members who identify with having lived experience.

The majority of services we spoke to did not have specific, dedicated funding to directly work to lived experience outcomes and it was often included in existing projects with no additional resource for both staff time and reimbursement for participation. There were very few examples of funding that included building an infrastructure to embed and support lived experience activities, or specific roles within organisations.

The resources that organisations used to inform their lived experience work were very varied, and included:

established toolkits and existing projects from other organisations (for example – Welsh Women’s Aid Survivor Network)

specifically commissioned research

learning by trial and error, drawing on staff experience

general approaches or frameworks for trauma informed practice, such as Hart’s Ladder of Children’s Participation or the Judith Hermann Trauma and Recovery Model.

Several of the services we spoke to either had a specific policy around lived experience, were currently developing one or had plans to develop one in the future. In the absence of a specific lived experience policy, mention was made of other policies that were relevant to the role participants were undertaking, such as a service user participation policy or group terms of reference.

About a quarter of services did not have a lived experience policy and did not say they were planning to develop one.

Almost all of the services we spoke to currently undertake or plan to undertake evaluations of their lived experience activities, with a mixture of formal methods, such as quarterly reviews, questionnaires and more informal evaluation of impact through observations, case studies and anecdotal evidence.

Supporting survivors

For the majority of organisations compensation for those taking part in participation activities was in the form of vouchers, food or gifts. Monetary payment was less common. One service said they had deliberately chosen to not include information on the expenses that they would be providing while they were recruiting for the project so as not to skew participants’ motivation for taking part, and because of the potential risk around financial exploitation.

Most services stressed the importance of providing wraparound support for people involved in lived experience or participation activities, with emotional support a key requirement. Several services provided one-to-one or group supervision or support, while a smaller number provided counselling or clinical supervision. For those currently accessing a service, key workers were also available to offer support.

For the majority of services, this type of support was not automatic but rather it was based on the direct needs of the person. A few examples were given whereby counselling, clinical supervision or other support was offered to participants after involvement, where there had been triggering or upsetting discussions or questions asked. However, this was not routinely offered, differing from many organisations policies for staff members.

Just under half of the services we spoke to said that they provide inductions for their participants, with a similar number providing training (either internally or externally).

Many organisations spoke of how they enabled people to engage in participation work. Some examples of good practice we heard include:

Wraparound care, pre and post briefing for consultations

Safety plans and safeguarding measures to ensure confidentiality

Hotels, travel, childcare

Interpreters and other needs met such as British Sign Language

The benefits

Services told us that participants can be positively impacted by getting involved in lived experience work.

This could look like:

Feeling empowered

Higher self-esteem

Impacting decision making

Owning their situation/Reclaiming their narrative

Increased confidence

Understanding their voice is being heard

Being understood and respected

The benefits of lived experience work for organisations were:

The upskilling for participants, particularly in areas such as leadership.

Increasing participants’ employability or allowing them to move from being a volunteer to being employed.

Enabling participants to feel connected with others, either through direct peer support and building positive relationships with other women or else through helping to improve the experience of other survivors.

Staff benefited from working in services that are shaped and informed by the survivors they work with.

Organisations/services having an increased awareness and enhanced understanding of experiences through a survivor lens.

The challenges

The key challenges in undertaking lived experience work identified in the exercise were:

What would help?

We asked participants what would help when carrying out any lived experience work:

Funding (developing peer mentors, internships, and peer researchers)

Training & knowledge building (participation, co-production)

Good practice principles

Creating case studies and evidence for funders and organisations to demonstrate impact

Support for staff with vicarious trauma

Networks to share practice and learn from specialist organisations

Robust policies

Next steps

Over the coming months, these findings will be used as a springboard to identify how survivors themselves would like to be involved in lived experience work and what is important to them. We will work with the SafeLives Authentic Voice Panel to understand their experiences of participation and what elements they think services need to consider when designing and delivering this work.

We will also be engaging with professionals working across a wide range of policy areas to gather information on what support is needed to embed survivor voice and lived experience into system and service design processes in a high quality, sustainable and trauma-informed way.

These methods of engagement will inform the Authentic Voice programme activities going forward. As this is a programme created and shaped by lived experience, we will be guided by what we hear from survivors and staff. We anticipate that our next activities will include:

Concern that lived experience work can be purely performative or tokenistic, and that more complex issues such as intersecting trauma are not covered.

Organisations not directly engaged with survivors may be hesitant to undertake lived experience work and are lacking in the capacity needed to do so in a safe and empowering way.

Significant resources are required if lived experience work is to be meaningful and safe, and therefore expectations need to be explored at the outset of any activity.

There are accessibility barriers relating to limited infrastructure and very remote populations, particularly in rural areas.

Lived experience work is often centred around service users, and not staff or professionals working within services which can lead to a divisive narrative of ‘othering’

Developing and co-creating tools and resources with women with lived experience of VAWG, trauma and adversity, to make sure pathways and support best meet their needs.

Facilitating a series of deep dive workshops with stakeholders to understand better what areas and organisations need to carry out lived experience work.

Producing a library of engaging content to highlight key learning and examples of good practice in embedding lived experience.